The Japanese keep meticulous, detailed accounts of their history, but kind of oddly keep those stories filed away. I don’t think it’s a conscious smoke screening—rather it may stem from the nation’s well-known reticence to promote.

History in Japan requires some sniffing out. Find the right tomes and websites, and you can learn the stories and people behind just about anything.

Moving to a new location deep in the countryside—whether you understand the Japanese language or not—makes me acutely aware of this greyness.

In the West, at least, we love to very publicly celebrate our history. We place placards on significant sites, tell stories, create museums, commission Hollywood biopics, and push legends onto whoever may listen.

The other day Toru and I were out walking Tera. We pressed a bit further south than our usual walks, into a neighboring valley neither of us had ever visited. When it was getting time to turn back home, we noticed an old hand-painted sign pointing to a local shrine up a small hill. No color as to what sort of shrine it was or why you would want to stop in, just a name: Matsugaoka Shrine (which fittingly means that it sits on a pine hill).

The Japanese countryside is rife with shrines, probably due to the agrarian nature of the Shinto religion. Matsugaoka is just one more of those structures—a village spiritual spot that presides over the life issues that the god (or gods) residing there take responsibility for.

Shinto is a practical, shop-for-what-you-need religion. There are an estimated eight million deities, each of which is assigned to “handle” any random matter you can think of, like pregnancy, house fire safety, plumbing problems, school entrance exams, earthquakes, typhoons, crop blight, rice harvests, cheating spouses, liver troubles, war, rainfall, throat infections, and real estate disputes.

Conveniently, each shrine lists the gods in attendance at that particular structure. Matsugaoka’s primary deity is Hachiman, one of Japan’s best known.

Hachiman (also known in times past as Yahata) presides over battles and war, but of more importance to remote valleys today he also blesses fishing hauls and crop harvests. Japanese Wikipedia tells me that there are 44,000 Hachiman shrines in Japan, second only to shrines honoring an even bigger headliner, Inari.

Matsugaoka Shrine is spotless. We didn’t see a soul there that day, but clearly people in the village below regularly sweep up and check on things. There’s a small assembly space, an altar, a tended graveyard, and even a gleaming single public toilet.

Nothing about the shrine is ornate. It is a minimalist Shinto shrine in the countryside…except…

There are two (expensive looking) black marble signs in front stating that Matsugaoka is sponsored by Shiseido, the cosmetics giant.

Now why is that, we thought. Most shrines do not have a corporate friend attached, and why would this quiet shrine on unremarkable hill have a global beauty powerhouse taking an interest?

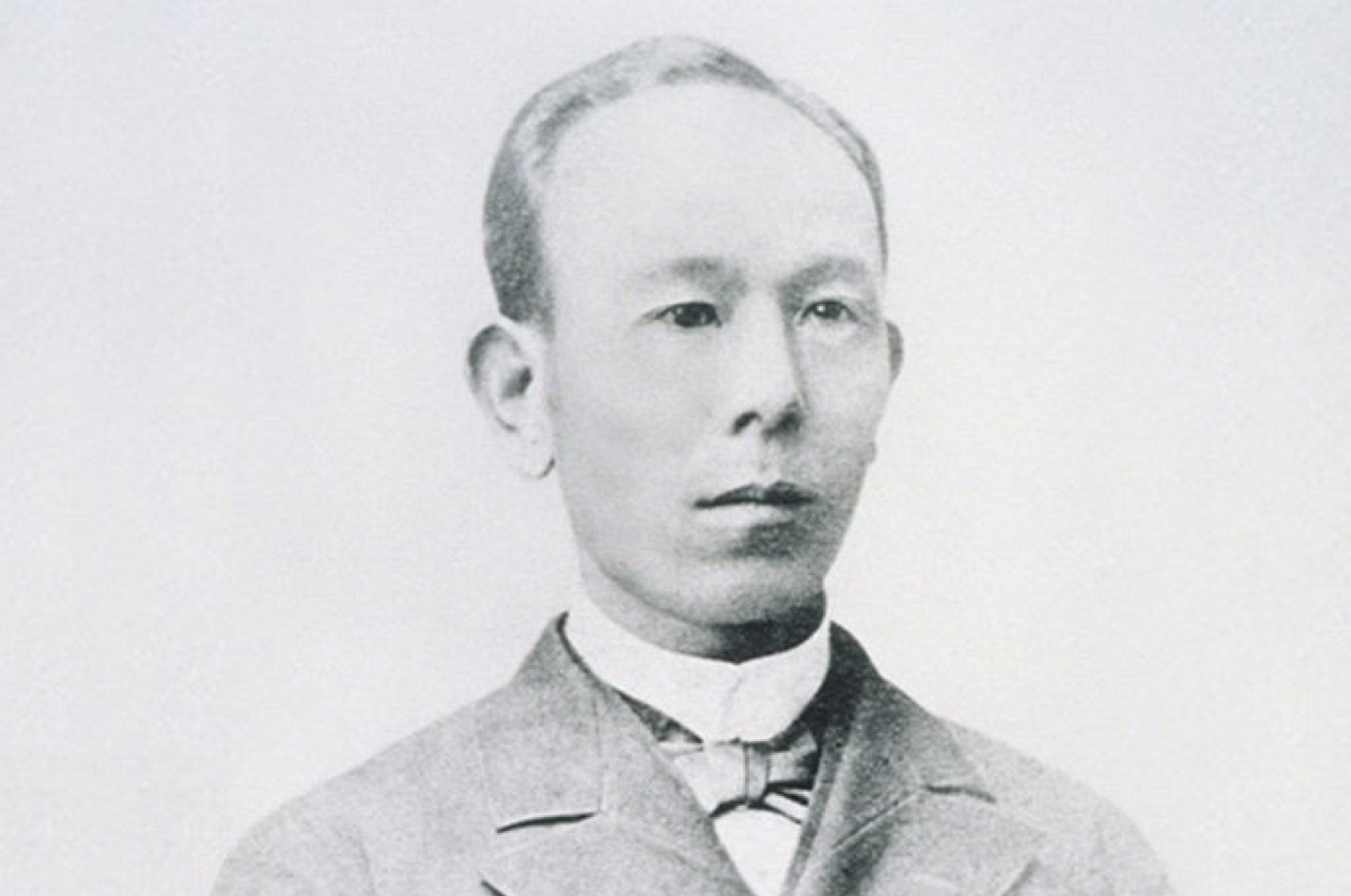

Turns out, the founder of Shiseido was a man named Arinobu Fukuhara, and he was born in 1848 in the tiny village that Matsugaoka serves.

I was immediately intrigued. I knew that I had to do some digging on this man.

1848 was the second year of Emperor Kohmei’s reign. It was also 20 years before the Meiji Era which we now recognize as the beginning of modern Japan.

This would have been a hard time to live in these valleys—nothing but ships or weeks-long circuitous foot travel connected these lands with the capital. Magnificent (and terrifying) Mt. Fuji looming across Sagami Bay was still literally considered to be a god then.

Arinobu began his career in the military and ultimately rose to become Chief Pharmacist of the Japanese Imperial Navy. It was in retirement that he felt that Japan needed a global-level pharmaceutical infrastructure, so as a second career he launched Shiseido Apothecary in the Ginza area of Tokyo. Of course that firm eventually diversified and became the cosmetics giant we know today.

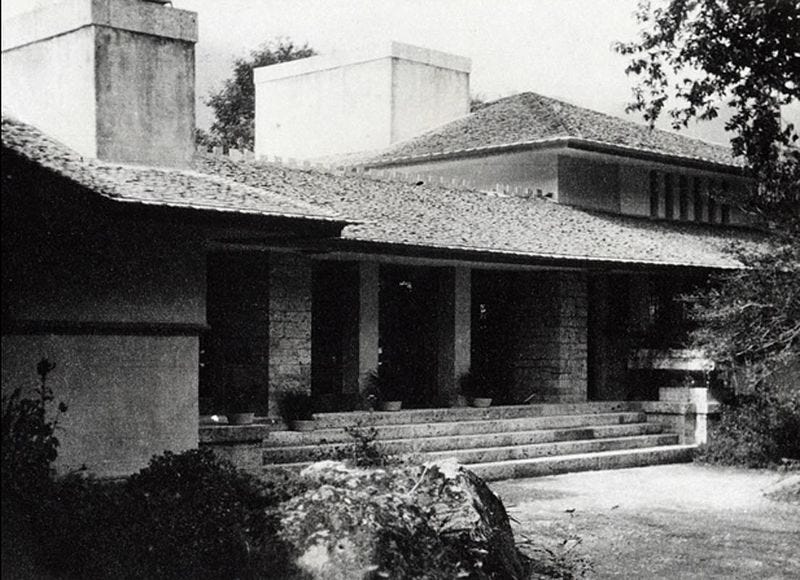

Sidenote. I am an architecture lover, so I was excited to find that Arinobu is also well known for commissioning a holiday home from Frank Lloyd Wright, which was then built in Hakone outside Tokyo. The Prairie Style home unfortunately was demolished by the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923, a year before Aribnobu died at age 75.

Arinobu’s sons and grandsons went on to lead Shiseido to unbelievable heights and interestingly are also credited with launching the photographic arts in Japan. The patronage and enthusiasm of at least three generations of Fukuharas fueled a national fascination with photography that survives to this day.

All that started just down the road from Frog’s Glen.

Really fascinating. And so Japan. Would love to have seen the FLW house…

I love connected and contextualised snippets of history. The soaring heights, the pithy residue post history’s grind. In a small shrine, in a small, albeit frog-noisy on occasion, glen. Nice.