Tsuyoshi Nagai fastened his silver cufflinks. These were his favorite pair, set with blue Murano glass stones. The collar of his professionally starched white shirt was stiff as cardboard.

Tsuyoshi hand-tied his Banderari black silk bowtie tight around his neck, and giving himself a once-over in his mirror, spread the ends and straightened. A red and gold silk Comme des Garcons vest, Tsuyoshi’s most prized piece of clothing and one he could barely afford, completed his uniform.

It was 2:00pm and almost time for him to leave his one-room apartment for the bar he ran alone in the center of Kasumigaseki.

Tsuyoshi was 47 years old. Though of average looks, he took great pride in keeping himself trim, physically clean, and impeccably dressed. While a spotless shop is a given in Tokyo, he often reminded himself that a bar is much more than a clean counter. The bartender’s own hygiene and presentation sends customers an unmistakable message of professionalism.

Thursday nights could see a few more customers than usual. President Takeuchi from the trading company upstairs in the same building might drop in for a Brandy Alexander nightcap after dinner with customers. The two baby-faced (and very loud) American equity traders from the securities firm across the street might pop by for post-market Martinis. Thinking of those kids, Tsuyoshi smiled to himself. One orders gin, one orders vodka…and the usual argument about which James Bond drank would ensue between them.

An entirely new customer could always appear, but it wasn’t likely. Like many sole proprietors, Tsuyoshi preferred to rely on slow word of mouth from regulars, rather than promotions or displays.

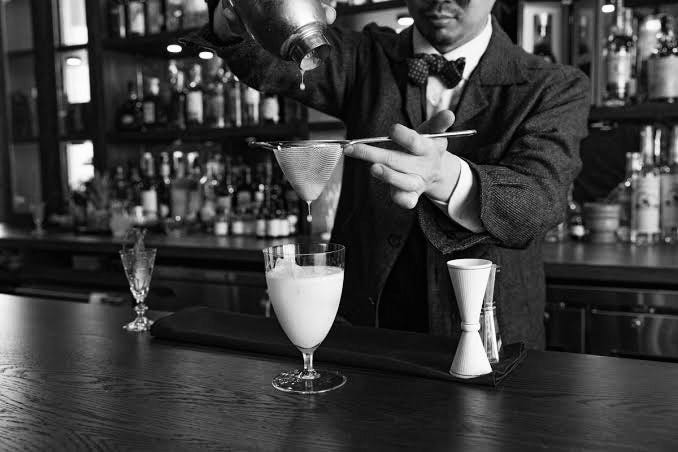

Tsuyoshi’s bar, staked by a few investors who got to know him from his former position at the Old Imperial in Hibiya, seated just five customers. The interior was dressed throughout in hand-polished maple and teak, dark brown leather, and spotless brass fixtures. With the exception of a wide French antique mirror backing the bar, no other adornments were noticeable. Ambient lighting was dim with the exception of pinpoint, perfectly targeted white spotlights positioned above each customer’s cocktail. The effect—just as Tsuyoshi intended—was of a bar attended by beautifully constructed drinks, rather than by the shadowed customers sitting before them.

After stopping by his favorite supplier for a replacement bottle of Armagnac, it was 3:15pm by the time he arrived at the bar to begin prep. As he reached into his pocket for keys to unlock the door, he noticed a stray thumbprint on the bar’s brass name plaque. Tsuyoshi took his handkerchief from his back pocket, breathed on the metal, and rubbed the smudge away.

Gaslight was his bar. Tsuyoshi had seen the Cukor film in his college years and was dumbstruck by Bergman’s ivory like beauty. As a young man he often daydreamed of one day owning a bar in which glamorous people like her as well as Boyer and Cotten would choose to hang out.

At 3:45pm, precisely on time, Murayama-san the ice purveyor stopped in to make his daily delivery of two 2-kilogram blocks. He was a chubby and gregarious young man, who in keeping with his blue-collar profession, always wore a black rubber apron and a hachimaki head band. As he shoved Gaslight’s door open with his hip and thigh, he loudly called out “Good morning,” an inside josh that nighttime workers in Japan often exchange. “Morning,” said Tsuyoshi as he laid out fresh hand towels and his ice picks so he could quickly get to work.

The blocks first needed to be busted into fist-size chunks which Tsuyoshi then meticulously chiseled and carved into perfect glossy balls sized to just fit into whiskey tumblers. Every late afternoon before doors open, Tsuyoshi produced five balls. Should more be needed during a busy night, he would carve additional orbs while conversing with customers.

Murayama Co. specialized in ice made only from spring water sourced in Shizuoka. They also used a flash freezing process that prevents clouding of the product. The shop’s finished blocks were as clear as glasses of water. Murayama-san was the first supplier Tsuyoshi telephoned eight years earlier when he knew he would open his own bar.

A customer once complimented Tsuyoshi on the beauty of his drinks, particularly noting his eye for details like ice. But he added that he “wouldn’t even notice” a few cracks or frost clouds if the Scotch is great. Tsuyoshi smiled getting the point, but said, “The problem is I would.”

Murayama-san brought the ice blocks behind the bar and set them on Tsuyoshi’s counter. As he turned to leave, he said with a wink, “You can pay us end of the month, Prize Winner.” He always called Tsuyoshi that, giving a friendly knuckle rap to a small framed photo of a much younger Tsuyoshi shaking up a cocktail. A tiny plaque below the frame read “Top Up and Comer 1965, Japan Kansai Bartending Regional.”

He was only 22. Tsuyoshi that day had made what the judges called a “sublime” Gin Fizz. He then followed that up with a notoriously difficult Color Changing Sunset Margarita. He never spoke on his own about the award, but Gaslight customers knew he took true pride in the achievement.

Until just past 9:00pm that night, Tsuyoshi was alone. With time on his hands he put a damp dust rag to Gaslight’s bottle collection. He then polished glassware and re-tidied the shop’s tiny restroom. Billie Holiday meowed through two old JBLs about men, gin, and whiskey.

Just past the hour Kuniko came in alone. She had already been out elsewhere and, though slurring somewhat and visibly fatigued, was hoping to chat over a final nightcap. She plopped onto a stool and splayed her arms onto the bar before her. Slumping her face into the polished counter, she groaned, “Nagai-san…why do men act so dastardly?”

Tsuyoshi liked Kuniko a lot. From what he could gather, she worked at an import-export business and was successful—much more so than any other female he knew in those days. She was quick witted, outspoken, and at times bawdy, a combination likely undermining her efforts with most Japanese men. Tsuyoshi suspected that although she was a catch Kuniko may be single for life.

Kuniko most every day wore warm-colored Max Mara couture. (She had a personal color analysis done at a friend’s suggestion and indeed the tones suited her.) She was a terrifying driver who inexplicably loved performance cars—she often drove her manual-transmission Porsche roadster on high speed, spur-of-the-moment weekend adventures to coastal towns to enjoy local delicacies. Tsuyoshi remembered her once blurting out on a random Friday evening, “Oh my gosh, second week of April! I need to hit Numazu tomorrow for Sakura shrimp rice cakes and sand dab soup.”

“Give me what you suggest for a spurned, still-young lady, Nagai-san,” she said. Tsuyoshi reached up and brought down a bottle of Calvados. He poured the amber liquid into a Lalique crystal glass hand-etched with dancing nymphs. “Apples are from the Loire,” he said.

Kuniko took a sip. “Oh, wash my blues away,” she said approvingly, and then took a pack of Virginia Slims from her purse. Tsuyoshi reflexively set a crystal ashtray before her and produced an old Dunhill lighter from his pocket. He applied the flame.

“Thanks, Nagai-san. This lady appreciates you.”

A second customer, and another regular, then entered the bar. Morishita-san was a handsome young man of about 30 who worked for a life insurer in the Kasumigaseki Building nearby. As he took off his overcoat to hang on a rack inside the door, Morishita-san asked for a Negroni on the rocks.

Tsuyoshi disagreed that match making is part of a barman’s duties, but he did believe that the sparking of conversation can be an invaluable service. Rather than place Morishita-san further along the bar, Tsuyoshi motioned for him to sit two seats down from Kuniko. He slid a coaster into the spot, gave it a purposeful finger tap, and said, “Irrashaimase.”

Transporting.

All I can say is "More, please!" The details and pacing alone had me right there till the end. If this were the beginning of a novel, I would pay for the rest.