I know what you westerners say. You think Japanese are superstitious, that we believe all manner of things, none of which are based on science or fact. Well, what you derisively call mumbo jumbo, I know to be “folk wisdom.”

Permit me to introduce myself. I am Kazutaka Sasama, eleventh generation fortune teller. My family harks originally from the misty, low-lying hills of southeastern Miyagi. We have counseled daimyo and shogun, as well as the uppermost echelons of the merchant class from the Edo Era to now. I myself have lived across Japan, from Kagoshima in the far west to a bear-hunting village on the Noromi Peninsula in Hokkaido—one of Japan’s iciest and most isolated points.

My 78 years divining the prospects of all manner of people have taught me that putting common sense first––by taking proactive steps that guard against evil––we can secure the futures of people, businesses, even entire villages and cities.

I want to tell you about the small town of Umizaki. Its people learned of terrible misfortune that had gained a pernicious foothold in their village. But working together, the village’s people altered what had first seemed an inescapable curse.

Umizaki is perched on the stormy, exposed coast of Iwate Prefecture. The 400 or so people there focus primarily on farming vegetables in the temperate months and on fishing sea bream and mackerel almost year-round. Oyster and nori farms have also provided important income…you may have heard of Umizaki Pink Belly oyster. It is known to have fetched top price in annual auctions!

Sadly, about 15 years ago the town without warning fell on hard times.

Fish catches plunged by more than half, while potato and onion crops became sick with a fast-spreading mold. Oyster populations more than halved. A small fabrics weaving and dying factory that had once provided steady employment closed. A wildfire also broke out one summer in the hills, destroying hundreds of acres of timber that Umizaki counted on for construction and income.

Everything seemed to go wrong for Umizaki at once.

The people loved their village, so they tried hard to address their challenges. But over time, the town’s fortunes continued to erode. Families began to move away and over several years the population entered a steady decline.

One day a traveling priest walked into town. Umizaki’s mayor, a man named Teranuma, explained to the priest the struggles the village was having. He asked the quiet visitor if he could “read the air” and give any advice to the town.

The priest said Umizaki’s fortunes may be being hurt by a number of causes. He would have to stay for a few weeks to understand better what specifically ailed the village. The priest took up temporary boarding at the town’s local temple.

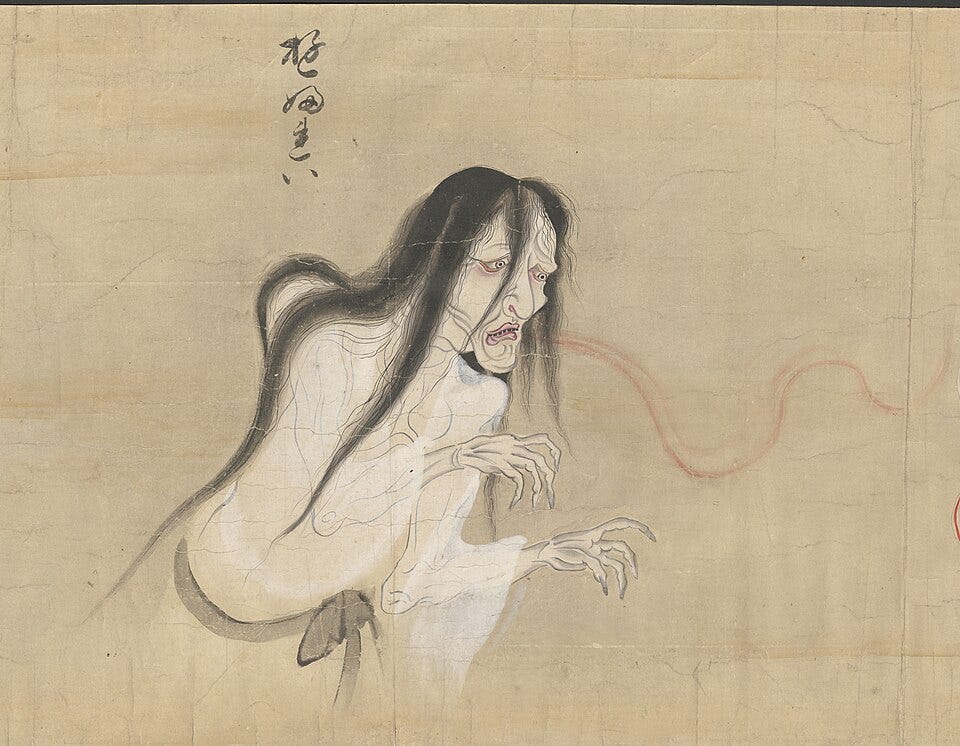

The priest spoke to many villagers. He inquired about their experiences and about anything new that had happened in the town. He chanted and prayed several times a day, and over time, he began to strongly sense the presence of malicious spirits.

On his third week in Umizaki, the priest called together the mayor and several of the village’s elders as well as senior fishermen and farmers. “I believe I have located the source of Umizaki’s troubles,” he said. “You may remember that three years ago an American joined your village, a young man named Peterson.”

“I knew it,” cried Yamada-san, the town’s paint store owner. “I just knew when that American came to our village we could be in for a world of trouble!”

Motomura-san, pilot of the sea bream boat Ichinohana Maru, nodded and crossed his burly arms tightly across his chest. “I also had misgivings,” he grumbled. “Peterson-san is a nice enough young man, but nothing ever comes from outsiders join–”

The priest held up his hand, stopping Motomura-san mid-sentence. “Now, now. One moment, everyone, please.

“While Peterson-san is at the heart of what I will explain to you, I wish you to understand first that none of this is his conscious doing.”

The priest then explained that the American had unknowingly attracted bad spirits to Umizaki. “This was certainly not the foreigner’s intention. Rather, I believe that your village, you, bear the brunt of responsibility. In not guiding Peterson-san carefully enough as he made a home here, Umizaki brought these visitations on itself.”

The priest continued. “Look. Peterson-san is just being himself, and being foreign, he is a walking target for evil hauntings. He doesn’t know many basic behaviors that serve to keep people safe.”

The priest then gave specifics. He said that for instance Peterson-san placed his bed with the pillow end facing North.

A gasp went through the room. ‘NORTH PILLOW?!’ one townsperson yelled in shock.

The baker Mochizuki-san raised both her hands to her mouth and whispered, “Unbelievable.” As if hugging herself to keep warm from a sudden chill, she said, “The number of deceased souls that must have climbed through his window on moonless nights and attached themselves to his back.”

She wept into her hands, “He must have carried those unwanted visitors everywhere through our town.”

“There’s more unfortunately,” the priest explained. “I asked him, and Peterson-san told me he sees no issue with cutting his finger and toe nails at any time. Even…in the...”

“NIGHT?” yelled Saito-san, the snow pea farmer. “What’s he thinking? Does he want to die before 30?”

Mayor Teranuma simply shook his head and muttered, “I pray both of Peterson-san’s parents are still alive. Most likely however these careless personal care practices long ago dispatched them to the beyond.”

The priest continued, knowing that he needed to tell the town the full extent of its issues. “When I visited his apartment, I wanted to observe Peterson-san in his natural state. He stepped repeatedly on the embroidered borders of his tatami. He also told me he hangs laundry out to dry at night. He somehow believes there are no bad persimmons. He swallows watermelon seeds. And he has many times stepped on the door and gate jambs of temples because he thinks ‘it is fun.’”

It was all too much for the villagers. An icy shock fell over the room. The room fell dead silent, each townsperson’s mouth agape…the only sound audible was a clock’s second hand ticking on the back wall.

The scale of Umizaki’s haunting had become clear. Then everyone began to panic at once.

“Demons are summoned––they’re surely here now!”

“His children will be disabled…”

“Thieves are among us!”

“It’s a wonder our village hasn’t burned to the ground five times already.”

“A watermelon must have sprouted from his belly button!”

A long, piercing shriek then filled the room. It was Sakakibara-san, the town’s seamstress widow. Tears were running down her face. Oka-san the gas station owner quickly sat next to her and began fanning her brow with a pamphlet.

The priest could see that the room had filled with a rapidly rising anger. The villagers seemed moments from taking up torches against the American.

The priest knew he had to switch gears. He spoke soothingly.

“Everyone, I know this has been a deep shock. But let me assure you. I am certain that Umizaki can find a solution that puts this situation right.” He encouraged all the folk to work together to devise a solution.

The townspeople knew that any attempt to confront Peterson-san or to eject him from the village would only backfire. Spirits and plague would dig even deeper into Umizaki’s fabric and remain for an extra 14 years. Rather, they needed to gently, indirectly help the American reverse the damage himself.

They decided that the best approach would be to covertly train Peterson-san to correct his own missteps without alerting him to the effort.

Mayor Teranuma hit on an idea. He would tell Peterson-san that Iwate Prefecture had a new revitalization program aimed at attracting and keeping new residents. Part of that initiative provides free housekeepers who can make life in the new town less stressful for newcomers.

In reality though a maid placed in Peterson’s “employ” would actually be a plant from the town!

“Whoever we choose could keep an eye out for Peterson-san’s missteps and gently make corrections,” he suggested. “She should never explain why she was correcting his affronts, but instead give plausible reasons for the American himself to change course.

“It’s a clever and wise idea,” said Kikuchi-san, a 67-year-old oyster processor. She then volunteered for the role, saying, “I admit it is a deeply frightening assignment, getting so close to what must now be an encampment of afterlife spirits having nightly ‘dinner parties’ in that young man’s apartment.”

She stood from her folding chair. “But I see it as my duty to our beloved Umizaki. I will do the work gently but diligently. We need to begin right away shooing these spirits and clearing the bad juju that has festered here so long.”

The room erupted in applause, moved by Kikuchi-san’s great courage. Everyone snapped their fingers three times in unison. Then to formally seal the pact, small packets of salt were distributed to each villager who then tossed two pinches over his or her left shoulder. The room crisply clapped their hands in unison three times.

The plan went very well. Kikuchi-san visited Peterson-san’s home each day, and in addition to cleaning and grocery shopping, made corrections to every infraction she found.

She convinced the American that pointing his bed’s headboard West would bring the stars into view each night. “What a waste it is for you to close your eyes each night, last focusing on this desk lamp when the heavens twinkle above from this large window.” Each time Peterson-san left his chopsticks stuck upward in his rice (summoning a cemetery’s worth of ghosts to take up residence in his living room), she quietly removed them and laid the utensils down beside the bowl. “Chopsticks are happiest horizontal,” she said. Peterson-san rolled his eyes but followed the direction.

She planted nantan berry plants at the apartment building’s entrance. Peterson-san loved the new bushes, although he was oblivious to the lost and wandering Dead that they were blocking from entering his hall.

One day while dusting, Kikuchi-san found a newly framed photo of Peterson-san and two lady friends on the desk in the apartment’s small study. Horrifically, the American had allowed himself to be photographed in the middle of the group of three. “Oh my, this boy truly wants to perish soon,” Kikuchi-san thought to herself. She “accidentally” knocked the frame to the floor and apologized later for having ruined the photo and frame.

Actually, she carefully removed the cursed photo, folded it three times, and then took it to the local temple for ritual bonfire disposal.

And of course when she found Peterson-san dressed one day with his happi coat wrapped right side over left like a corpse at its own wake, she coaxed him to reverse the overlap, saying that he looked “so much more handsome this way.”

The results came quick. Spirits and other nefarious demons climbed off Peterson-san’s back, stopped riding on his shoulders, and left his home. Countless more ghosts wandering greater Umizaki returned to their urns and tombs.

The fortunes of the village rebounded, with fish catches surging and crops bountiful once again. Wildfires stopped, and the once-closed fabrics factory reopened with jobs that needed to be refilled.

The villagers quietly hailed Kikuchi-san as a heroine. One by one the townspeople brought her small, hand-wrapped gifts of gratitude for the selfless efforts she had made on behalf of all.

With the foreign resident now in check, and none the wiser to the herculean effort made behind the scenes to seal the afterlife vortex he had unknowingly created, the fortunes of Umizaki continued to rebound. Kikuchi-san stayed on as the maid, now needing only to make small adjustments to Peterson-san’s behaviors.

He now wore his yukata robe correctly, his chopsticks were laid down rather than stuck devilishly in his rice, he slept with his head West (quite auspicious!), and he purposefully stepped over each of his tatami mats’ sewn borders.

For Pederson-san’s 25th birthday, the maid gave him an English language translation of a Japanese children’s book of folk wisdom. Kikuchi-san knew that the American was now well under control and free of ghostly hauntings, but she thought the beautifully illustrated picture book would be a fine way to keep teaching Japanese wisdoms without Peterson-san becoming aware of the lessons.

He loved the book and read from it every evening. He learned that Spirits most often possess the Living by entering through the skin and nails of the thumbs, so when at funerals or near graves thumbs must be tucked into fists or hidden in pockets. He learned that rivers, oceans, and any other body of water is how the Dead travel at night between worlds, so no one should swim after the sun sets. And whistling tunes at night would only call more wraiths from their afterworld slumber into the land of the Living.

You may be aware that the late summer Obon holidays in Japan are something like Festivals of the Dead in other cultures. Like those celebrations, Obon is a happy event, a time when the spirits of deceased relatives and friends are welcomed back to hometowns to visit. Obon is a highly controlled event, nothing like the willy nilly unleashing of vengeful wraiths that Peterson-san had once brought upon his adopted village.

In his fourth year in Umizaki, Peterson-san invited two American friends to the town for the festival. He was excited to show his buddies the Bon Odori group dances, the processions in the streets, and of course the nighttime feasting and drinking among the villagers and guests.

He told Kikuchi-san of his plans and she felt proud that a foreigner wished to show off her village. She knew she would have to keep careful eye particularly on the friends, but even if there was a misstep what damage could be done to Umizaki by simple visitors?

The night before the festival his two friends, Josh-san and Kyle-san, arrived by train after a six-hour journey from Tokyo. They slept on futon on Peterson-san’s living room floor.

Saturday night was the main dance and festival at the shrine. Kikuchi-san had promised to visit Peterson-san’s apartment by 5PM to help the three boys dress and ready for the festivities, but by 6PM she had not yet arrived.

“It’s odd. She’s never late,” said Peterson-san. “But no big deal. I can help everyone put on their yukata robes and we will just head to the shrine ourselves.” The boys laughed as they donned the light cotton robes, gathered a few ice-cold cans of beers to drink along the fifteen-minute walk, and headed to the village center.

Back at her own apartment Kikuchi-san woke from her futon with a start. She hadn’t set her alarm correctly and realized her afternoon nap had run over. She saw that it was already almost 6PM.

“My lord. Americans have dressed themselves and are likely already at the festival. I must immediately get to the shrine to make sure all is well,” she said to herself in a panic. She left her house and moved down the road as quickly as an older lady could.

A growing dread filled her though as she hurried. She knew something was wrong. She further quickened her pace.

Kikuchi-san’s mobile phone buzzed. It was a text from Mayor Teranuma to her and a group of villagers that had been set up on the LINE app for any emergencies.

Three foreigners unattended. Entering shrine grounds now.

Maybe…okay…?

Kikuchi-san knew that Mayor Teranuma’s message meant this was explicitly not okay. She broke into a run and spoke out loud to herself. “Peterson-san will be fine. He will be. His robe will be left over right. His belt will be on his hips, not his belly. He will not be whistling a tune. But would he even notice if one of his friends has gotten things wrong? I doubt that! He wouldn’t even see. He is a foreigner!”

She was panting now. “Are all Americans magnets for wraiths? I will be blamed of course!”

“I’m not a damned miracle worker,” she shrieked to no one.

Kikuchi-san rounded the last town corner and entered the outer torii of the village shrine. She arrived just in time to see the three young foreigners laughing and making their way through the main wooden gates of the shrine. Just as one of the boys was about to step squarely onto the jamb of the shrine door, Peterson-san stopped him, explained something inaudibly, and all three carefully stepped over the jamb. Still many paces away and out of earshot, Kikuchi let out a relieved “Whew” when she saw the boys’ careful entrance.

Saito-san, the snow pea farmer, who was also watching warily a few paces away, whispered to his wife, “That’s at least four years of sweet potato blight averted, right there.”

The young Americans then went (quite correctly!) to the shrine ground’s communal fountain to wash their hands and to rinse their mouths with the fresh well water. Shrines are of course not to be entered when dirty.

Kikuchi-san kept her distance and continued to watch. Peterson-san coached his friends by demonstrating first. He used a ladle to pour spring water onto his hands. And then to rinse his mouth, he did not drink directly from the ladle like most any westerner would. He cupped his left hand, poured water from the ladle into his left palm and used that to fill his mouth.

The two guests did just as Peterson-san had demonstrated. Perfect!

Still catching her breath, Kikuchi-san smiled to herself. She had underestimated Peterson-san and his capacity to learn. She scanned the crowd and saw that the traveling priest had returned to Umizaki for the Obon Festival. He was also quietly observing the three Americans with a smile of relief.

Kikuchi-san and the old priest exchanged warm bows.

The evening went very well. All through the festivities, Peterson-san guided his visitors well. Kikuchi-san never had to even slightly intervene. The townspeople were overjoyed and all in the village enjoyed the Obon festival.

After the event, however, the visitors made a terrifying misstep. One of the worst imaginable considering the potential reach of its repercussions.

The boys were walking back to Peterson-san’s apartment tipsy and full, talking excitedly about the festivities. Each felt proud to have been welcomed to the village’s celebration and to have participated in the rural rites.

The August evening was muggy. Kyle-san, the youngest of the three men, saw the town’s river snaking next to and below the path they were walking, and he suggested a quick swim. Peterson-san demurred, but both Kyle and Josh descended to the river’s edge, took off their yukata, and wearing only underwear entered the cooling water. They splashed in the river and after about 10 minutes got out, dried off, and returned to the path back to Peterson-san’s apartment.

A few villagers saw the two boys playing in the water and ran immediately to report to Kikuchi-san and the old priest. “The Americans played in the river!” they yelled with ashen faces.

“They, what?!” Everyone froze in horror contemplating the transgression.

The old priest knew that there was nothing the boys could have done on a night of Obon that could be any worse. A river is a thoroughfare between the Land of the Dead and the Land of the Living for the spirits traveling to and from the festivals. The river would have contained a rush-hour’s-worth of commuting spirits all happy to hitch a ride on any human crazy enough to enter the water.

The two American boys must now be possessed with hundreds, if not thousands of back-clinging and shoulder-riding spirits, he thought.

“I’m afraid the damage is done,” said the priest. “And while I think Umizaki will be fine, as these are foreign visitors set to return to their home country tomorrow, we should be deeply concerned for America, their ultimate destination.”

The priest explained to the villagers that if nothing was done, the Umizaki spirits would ride the two boys’ shoulders and backs on the flight home and then, once in America, visit at least 12 years of terrible misfortune and destruction on that country. “The spirits will be out of sorts, distraught and angered by their unscheduled and far-flung destination. “They will summon fellow spirits from American cemeteries and soon the entire country will be in an almost inexplicable state of confusion and despair. I fear for the United States,” he said gravely.

But the priest had a plan.

On the next morning, before the boys’ departure back to Tokyo and their waiting flight back to America, the priest visited Peterson’s home. He caught the departing boys just in time.

He greeted Peterson-san and then quickly turned to Josh-san and Kyle-san. “I am so glad I caught the two of you,” he said to the boys. “Umizaki was very proud to host you on your visit. I have a small gift for you that I want you to take back home.” The priest gave each youth a small carefully wrapped box. “Inside you will each find one freshly baked warabi mochi, a chewy rice cake made of bracken starch. Warabi mochi is a special dessert that we first began eating in the Heian Period, in the year 900 AD.” He explained to Josh-san and Kyle-san that this was a very lucky cake and if they follow his directions carefully they and their families, even their neighbors, will enjoy many years of good fortune.

“But listen carefully. It is very important that you eat this cake once you are in America,” he said. “Do not eat it until then. Once you are back in your country, please enjoy,” he said with a warm smile.

“Oh, and for maximum luck you must eat it all,” he added. “Don’t simply taste it.”

The boys smiled and said they understood. They put the cakes into their bags and were soon on their way to Tokyo’s Haneda Airport where they would board an evening flight to San Francisco.

After the boys had left, the priest turned to the rest of the villagers. “Again, we are not in danger here, but I fear deeply for America. No country deserves what is now headed its way,” he said with a grave expression. “I sensed ancient spirits all over those boys. The seeds of strife, violence, and disorder will be landing in the States soon.

“Please, everyone, pray that the boys do exactly as I instructed.”

At San Francisco International Airport, Josh-san and Kyle-san made their way first to Baggage Claim and then to Customs, where the inspector asked both to open their bags. The inspector pointed to the mochi rice cakes and said, “X-ray shows these to be food products. I’m sorry but you cannot bring these into the country.” She lifted the small boxes out of the young mens’ carry-on luggage and moved to drop the two cakes into a garbage can.

Josh-san spoke up. “Could we eat these now, rather than you throwing them into the trash? They were gifts.”

The guard smiled and said that would be fine. “You just can’t bring them in, but go ahead, enjoy.”

Josh-san popped his cake into his mouth and began chewing. He loved the stickiness and the odd, grassy flavor of the warabi. “This rocks,” he said and he swallowed the treat with delight.

Kyle-san followed suit and began chewing. But he soon froze. “Oh Jesus, this is awful,” he said with his mouth still full of the gooey cake. He leaned just over the guard’s counter and spat the cake out in the trash.

The two boys continued into the main terminal and were soon on BART into town.

I need my own Kikuchi-san. Seriously, thanks for explaining what's currently going on in America! Now it makes sense.

That’s brilliant!